While writing about the new Google iPhone App and it’s voice recognition feature Tim O’Reilly made a comment on his blog, O’Reilly Radar, that I just can’t stop thinking about:

Cloud integration. It’s easy to forget that the speech recognition isn’t happening on your phone. It’s happening on Google’s servers. It’s Google’s vast database of speech data that makes the speech recognition work so well. It would be hard to pack all that into a local device. And that of course is the future of mobile as well. A mobile phone is inherently a connected device with local memory and processing. But it’s time we realized that the local compute power is a fraction of what’s available in the cloud. Web applications take this for granted — for example, when we request a map tile for our phone — but it’s surprising how many native applications settle themselves comfortably in their silos.

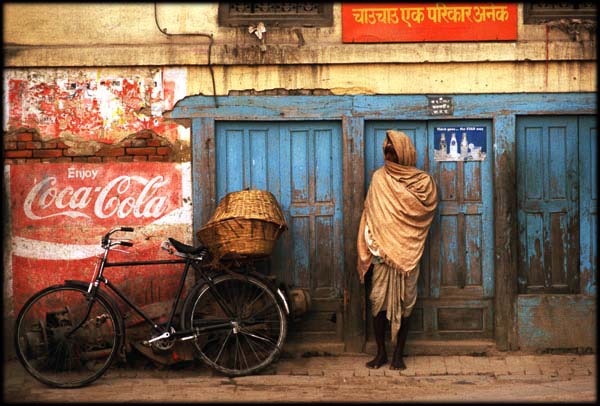

Admittedly, I have always been happy with the term ‘Cloud’ being defined as either ‘a mop headed Google geek’ or ‘the place my Gmail lives’ but it occurred to me, after reading Tim’s post, that the cloud has the ability to cause significant positive change in regions where mobile penetration is increasing, i.e. Africa, Asia, the Middle East, etc. While all the pieces had been floating around in my head for a while I am just now understanding that we really need to drag very little out to Africa for them to have incredibly powerful technology in the palm of their hand (and that such thinking is inherently poisonous) and that we are better off attempting to facilitate the connection of their handsets to The Cloud in order to assist with effecting positive social change.

With massive GSM penetration in places like Uganda it makes you wonder if we haven’t been missing the point for some time now. While Jeff Allen is slogging through a truckload of work down in Sierra Leone to bring a Health Information System online I sit here and wonder if the Swinfen Charitable Trust, Nokia Data Gathering and OSMTrack aren’t signs of better things to come. God knows we need guys like Jeff to put real, hard systems in place (that’s why I founded Humanlink) but I also cannot get over how much work I can get done on my iPhone and how little time I now spend at my computer.

Eduardo over at InSTEDD is already working in this direction with SMS GeoChat and although he’s currently focused on a very defined sector (diseases surveillance) in SE Asia I know they plan a worldwide roll out. While such a system has significant potential I see as much more disruptive applications like OSMTrack and Nokia Data Gathering as innovations that allow any user, for sometimes a nominal fee, to generate data and share it at will. (I should also throw in Nokia Sports Tracker as it also offers a very useful tool for collecting track data.) The only problem with such applications is that they rely on upper end phone models which are definitely not the norm in the developing world although I am confident that the penetration of smart phones into these markets will continue to increase.

If the general populace can collect data for their locations and post this information to open sites like Open Street Map then aid workers will have a repository of data to work off of if and when there is another emergency. The UN folks do a great job of pushing maps for humanitarian disasters but, as we saw with Georgia, maps take time to create and update so a much more proactive stance is required. I have already posted on the impressive amount of work put into creating maps for places like Kabul, Baghdad, and Tbilisi by people like Kevin Toomer. Compare OSM to Google Maps (or any other online source) in these areas and the results will astound you. These are the places we work and really the only places we really need maps for. In an emergency the first thing I always did was to build a dossier for the event location and maps were and integral part of that package. I didn’t have time to wait for Reliefweb to post updates and satellite imagery from Google Earth can only get you so far. What is needed is a very proactive approach to mapping by agencies and individuals in unstable regions.

Once that data is collected, whether it be GPS tracks or health data, it can easily pushed to the cloud from a mobile handset bypassing the whole download/upload routine. This makes me think of the Congolese health officer who Jeff wrote about who had terrible trouble producing reports for MSF from his desktop due to a virus and a shoddy connection which came through his mobile handset via neighboring Uganda. I wonder if the lion’s share of his data collection could have been done from a high end handset? Gone are the days of worrying about whether or not the generator is running virus on Windows machines. Now it is possible to carry your office in your pocket and with a collapsible solar panel you can motor on indefinitely. You don’t even need a network connection as you can simply upload the data once your are back within reach on your mobile carriers signal.

Dmitri Torpov is making $0.99 per download over at the App store for his OSMTrack and may also be doing a hell of a lot of good for future aid teams. If only one person takes their iPhone to the field and commits to mapping their tracks while going from health post to health post and then uploading that data via a local network (either while roaming or on a cracked handset) the world might just be a better place. My guess is that mapping Monrovia, Goma, Juba, etc. now will pay off in the long run. With the cloud hovering over Africa rapidly growing in size the advantage goes to those folks on the ground who have the power to generate the data and ultimately benefit from it.

{ 2 trackbacks }

{ 0 comments… add one now }